Women’s Day Is Making a U-Turn in China

By

Junjie Wang

Published on

March 10, 2025

Jingzhi Voice brings thought leaders, industry pioneers, and cultural influencers together to decode key trends, challenge conventions in China, and offer forward-thinking ideas that shape the future of jingzhi (精致) and beyond.

Joan Macdonald, a 70-year-old fitness influencer from Ontario, Canada, has unexpectedly become the face of a viral social media moment in China.

A striking poster of her flexing toned muscles in a pink Lululemon tank top, paired with the Chinese phrase “活出生动” (a nod to Lululemon’s global campaign, Live Like You Are Alive), has been widely shared on Xiaohongshu (Rednote).

Unlike past Women’s Day campaigns drenched in pink ribbons and glossy discounts, Macdonald’s image delivers a message of empowerment without resorting to commercial gimmicks.

Chinese consumers are taking note—and pushing back.

Beyond Pink Discounts: A Shift in Women’s Day Narratives

Something is changing in the way Chinese female consumers engage with Women’s Day in recent days. If spending power is a form of power, then Chinese women are wielding it with new intentionality.

Retailers, once dictating the language of the occasion, are now being held accountable by the very audience they target.

In Chengdu, a city known for its relaxed vibe and iconic pandas, shopping malls featured LED signs displaying quotes from renowned feminist writers, films, and local idioms celebrating women’s strength.

These messages—free of flowery adjectives and infantilizing nicknames—are gaining traction on social media. Clean, direct, and unapologetic, they stand in stark contrast to the saccharine marketing language that has long defined March 8th promotions in China.

For years, brands and e-commerce giants rebranded the holiday into “Queen’s Day” or “Goddess Day,” operating under the belief that these labels exuded respect while, in reality, they served as little more than ploys to lure female customers into spending. But Chinese netizens are reclaiming the real name.

On RedNote (Xiaohongshu), users are documenting and celebrating businesses across the country that have opted for a more powerful and yet de-commercialized approach.

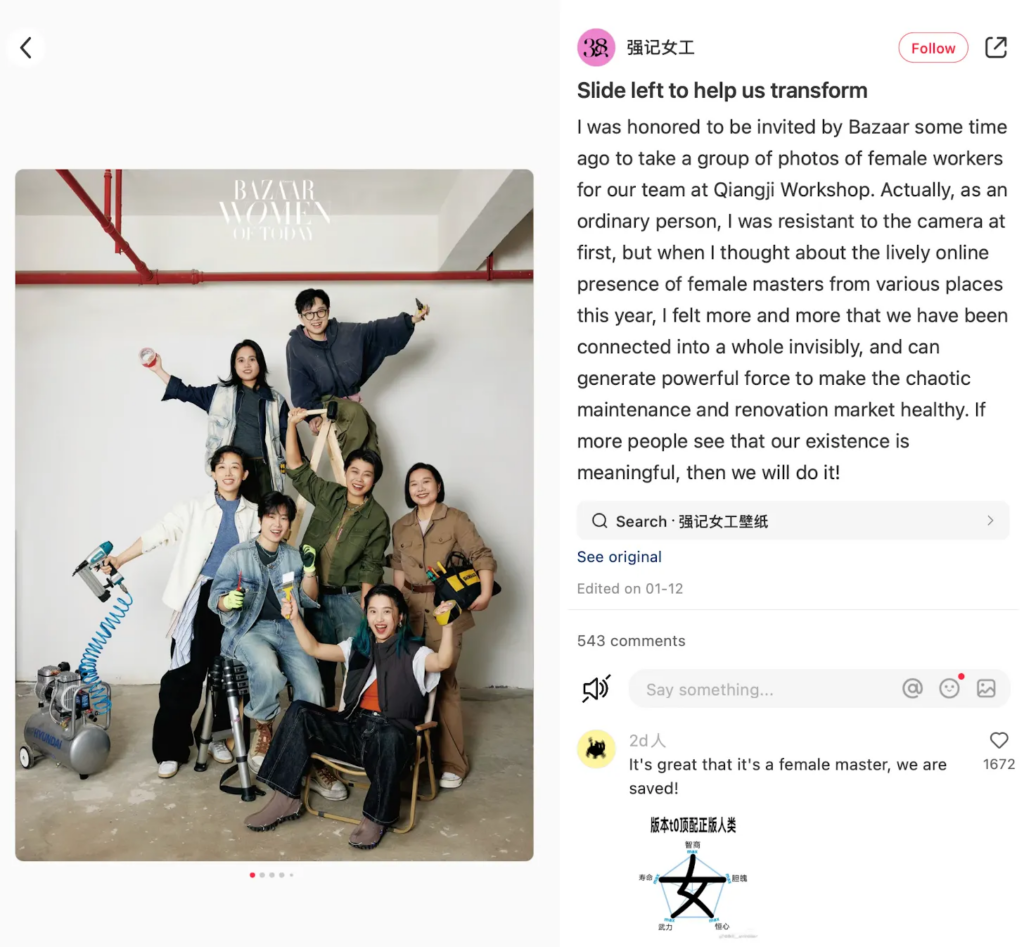

Photo: RedNote screenshot

It signifies a broader shift in consumer consciousness—a realization that the language used around Women’s Day reflects deeper societal attitudes toward women. The refusal to be infantilized, sexualized, or turned into a convenient marketing demographic speaks to a growing awareness of power dynamics in branding, advertising, and commerce.

The Rise of Women-For-Women Businesses

This shift in values has also catalyzed a new commercial model: the all-women business (or “women-for-women” business), referring to businesses both founded by women and catering exclusively to female consumers.

The emergence of this model isn’t coincidental—it is a direct response to long-standing gender imbalances in both professional and consumer spaces.

“Women-for-women” businesses can be categorized into two distinct types in China at the moment. The first includes tailored services designed exclusively for female clients, such as skincare clinics and women-only bars, which prioritize customer experience and comfort. The second type ventures beyond commercial viability into ideological experimentation—feminist bookstores, women-led home renovation businesses, and female-only electrician services.

These businesses are not just about filling a market gap; they represent a broader societal reconfiguration in how women engage with labor, power, and consumption.

Sure, questions remain about this emerging business model—some have fallen short or faced criticism. Yet, it undeniably signals a broader shift in consumer values among Chinese women, particularly in major metropolitan areas like Shanghai and Beijing.

Economically, this trend aligns with the “she-conomy” (she + economy), a term widely used in Chinese marketing discourse to describe the rise of female-driven consumer spending.

The numbers back it up: women control as many as 75 percent of household purchasing decisions in China, and their spending patterns are increasingly aligned with values rather than impulse-driven consumption.

This is why companies that embrace inclusivity, respect, and authenticity in their messaging are gaining traction.

Government Messaging: A Rare Nod to Feminism?

Across state-owned shopping malls from Chengdu to Shanghai, Zhengzhou, and Changsha, bold yet understated slogans that align with feminist discourse are appearing—an unusual sight in a country where feminist activism often meets governmental scrutiny.

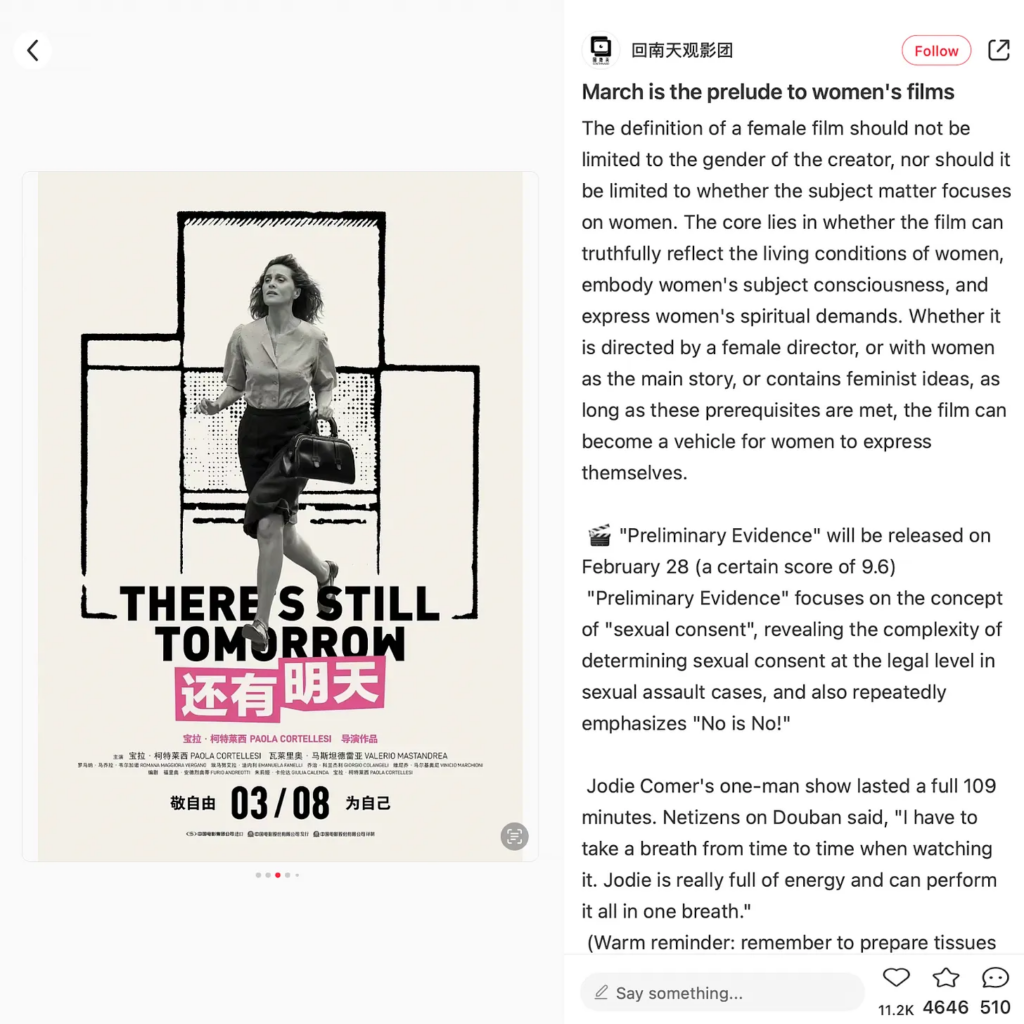

This March has also seen an influx of imported feminist films in Chinese cinemas for the first time, despite having been released abroad years ago.

Among them are There’s Still Tomorrow, an Italian film directed by Paola Cortellesi, Prima Facie starring Jodie Comer, the French animated film Fireheart, and several others—marking a rare cultural shift in how gender issues are discussed in the public sphere.

Photo: Screenshot

Historically, the Chinese government has been cautious about embracing Western-style feminist narratives. Yet, recent developments suggest a degree of strategic openness, likely tied to an upcoming global summit on gender equality and women’s empowerment, which China is set to host in the second half of this year.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi announced earlier this month that Beijing will hold the Global Leaders’ Meeting on Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment, signaling the event’s diplomatic importance.

While this does not signal an ideological overhaul, it does indicate that certain feminist themes are being cautiously permitted within controlled environments—especially when they align with broader diplomatic or economic interests.

The question remains: is this newfound space for feminist dialogue a temporary allowance for political optics, or does it mark a more enduring shift? Regardless, Chinese women’s increasing awareness and rejection of outdated marketing narratives suggest that, whether governments or corporations adapt or not, consumer behavior has already moved forward—and it isn’t looking back.

This is an opinion piece by Junjie Wang, a seasoned fashion business reporter based in Hong Kong. The views expressed do not reflect the official stance of Jingzhi Chronicle.

Formerly Senior China Editor at Vogue Business and Fashion Features Editor at Vogue Hong Kong, Junjie has years of experience covering fashion, retail, and lifestyle trends across China. With deep expertise in the Chinese market, his work offers valuable insights for global audiences.

Subscribe to his newsletter, China Retail Watch, for timely updates, comprehensive analysis, and forward-looking insights on China’s rapidly evolving retail landscape.